Writing Over Squares on Canvas

平面という物理的に平らな面の上に、なぜ人間は絵画という虚構の空間を描き続けてきたのでしょうか。

そのわけを私は「物質としての平面とイリュージョンとしての絵画空間」という二つの要素をもとに考えています。

片目をつぶって絵を見ると、描かれたものの遠近感が両眼で見た時よりも強調されて見えたり、立体感が感じられたりします。

人間が自分と対象物との距離を判断するのは、対象と両目それぞれとを結んでできる線が作る角度によってです。

片目で見たときは当然この角度は出来ません。

従って人はキャンバスまでの距離の知覚が不可能になり、キャンバスが平面であるという事実は経験的にはわかっているものの感覚的には知覚できません。

その分だけ平面上に描かれたイリュージョンが率直に知覚されるわけです。

逆に考えれば人間は絵を見ている時、キャンバスの物理的な平面を知覚すると同時に、その上に描かれたイリュージョナルな空間を知覚するという互いに矛盾するふたつの知覚を同時にしていることになります。

しかしこの矛盾こそが絵画空間を創り出している当のものであり、この矛盾による葛藤こそが絵画の複雑で魅力的な世界を創り出しているのです。

そしてこの物質としての平面とイリュージョンとしての絵画空間というふたつの要素の葛藤の様態の変化こそが絵画の歴史とみることができると、私は考えます。

セザンヌの取り組みも、モンドリアンの取り組みも、その根源はここにあるように思います。

カメラが発明されてからそれまで絵画の重要な役割であった、現実空間の再現という役割は重要なものではなくなりました。

現実空間の奥行きの再現という束縛から解き放された近代絵画はその新しい姿を求めてはげしく変遷し始めます。

セザンヌのサン・ヴィクトワール山を描いたシリーズの後期の作品では前景、中景、後景同士の間の空間がどんどん縮んでいきます。

同時に筆致が生み出す地と図の関係が固定されず、これが浅いながらも豊かな絵画空間を生んでいきます。

プーシキン美術館にある池を描いた作品では、画面がほぼ緑一色の抽象画のようになります。

奥行きは更に浅くなりますが、絵画空間は豊かさを増していきます。

ニュアンス豊かな緑の色面が創り出す地と図は相互に入れ替わりながら、何時間見続けても飽きない豊かな絵画空間を創り出しています。

モンドリアンの林檎の木を抽象化していったかの有名な一連の作品も地と図の関係が絵画空間の重要な要素になっています。

その後、幾何学的形態にまで到達した作品では、支持体の物質としての平面とその上に描かれたイリュージョンとしての絵画空間がほぼ同じレベルまで近づいていますが、物理的な平面よりも絵画空間の方はまだ少し奥の方にあります。

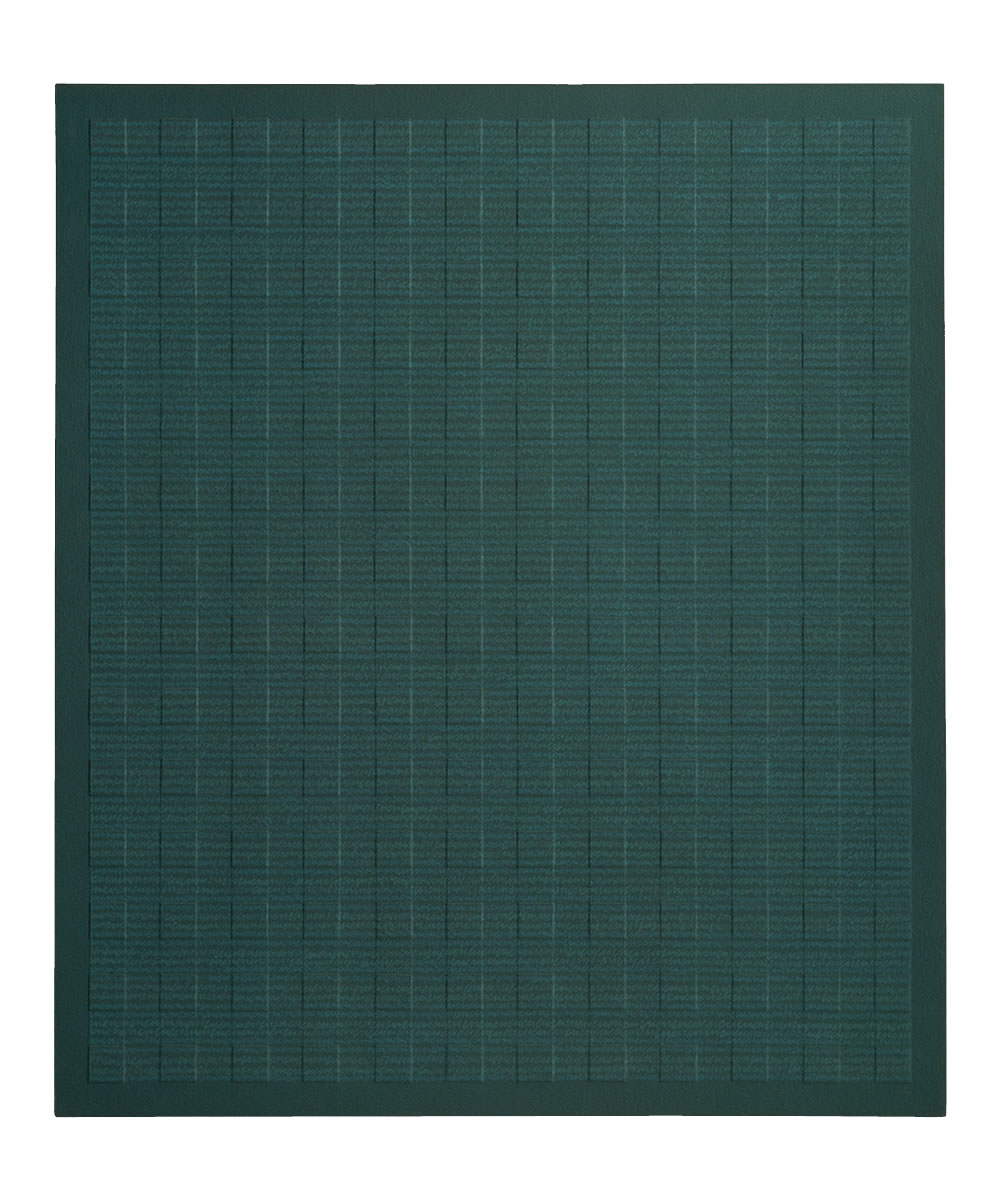

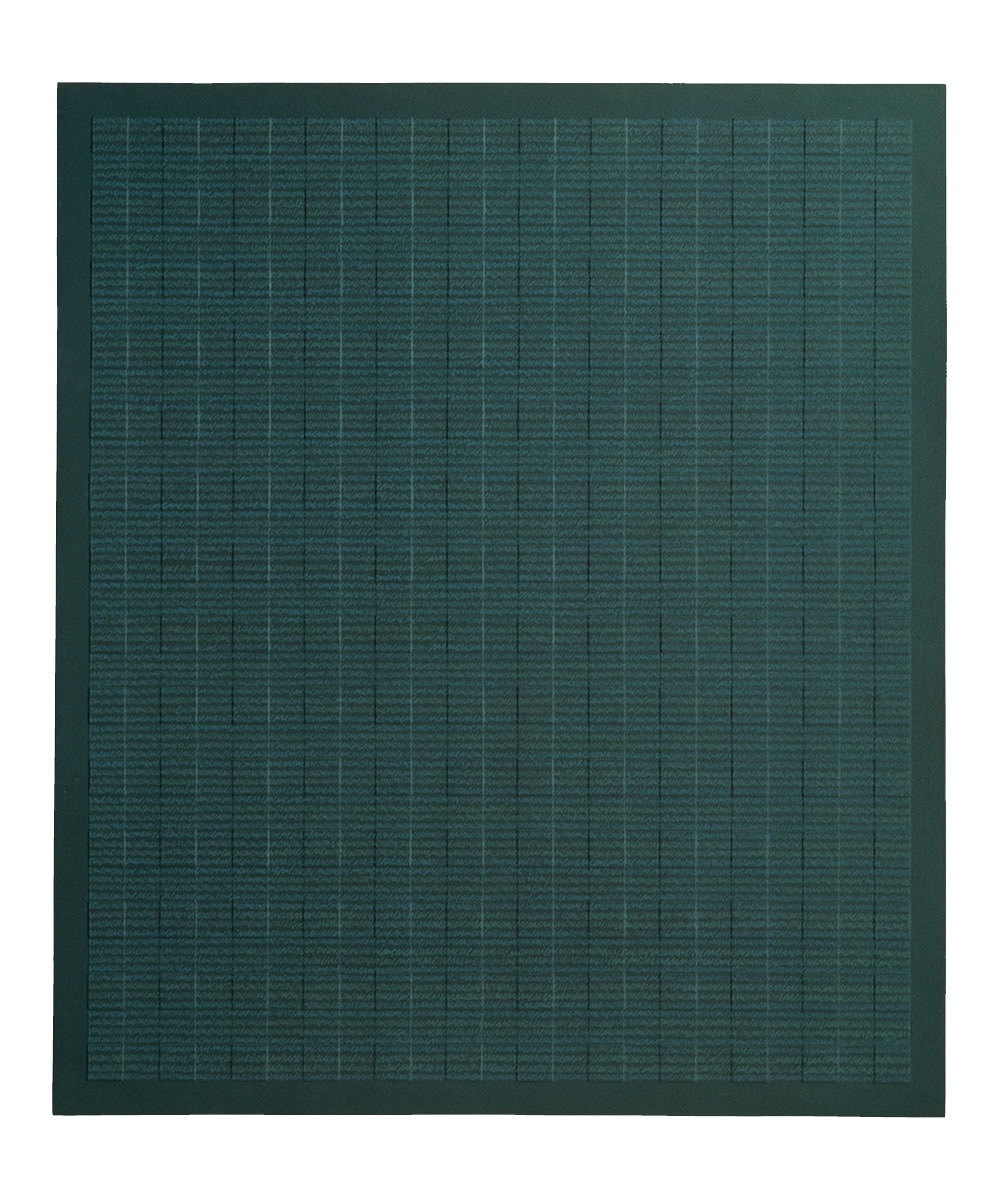

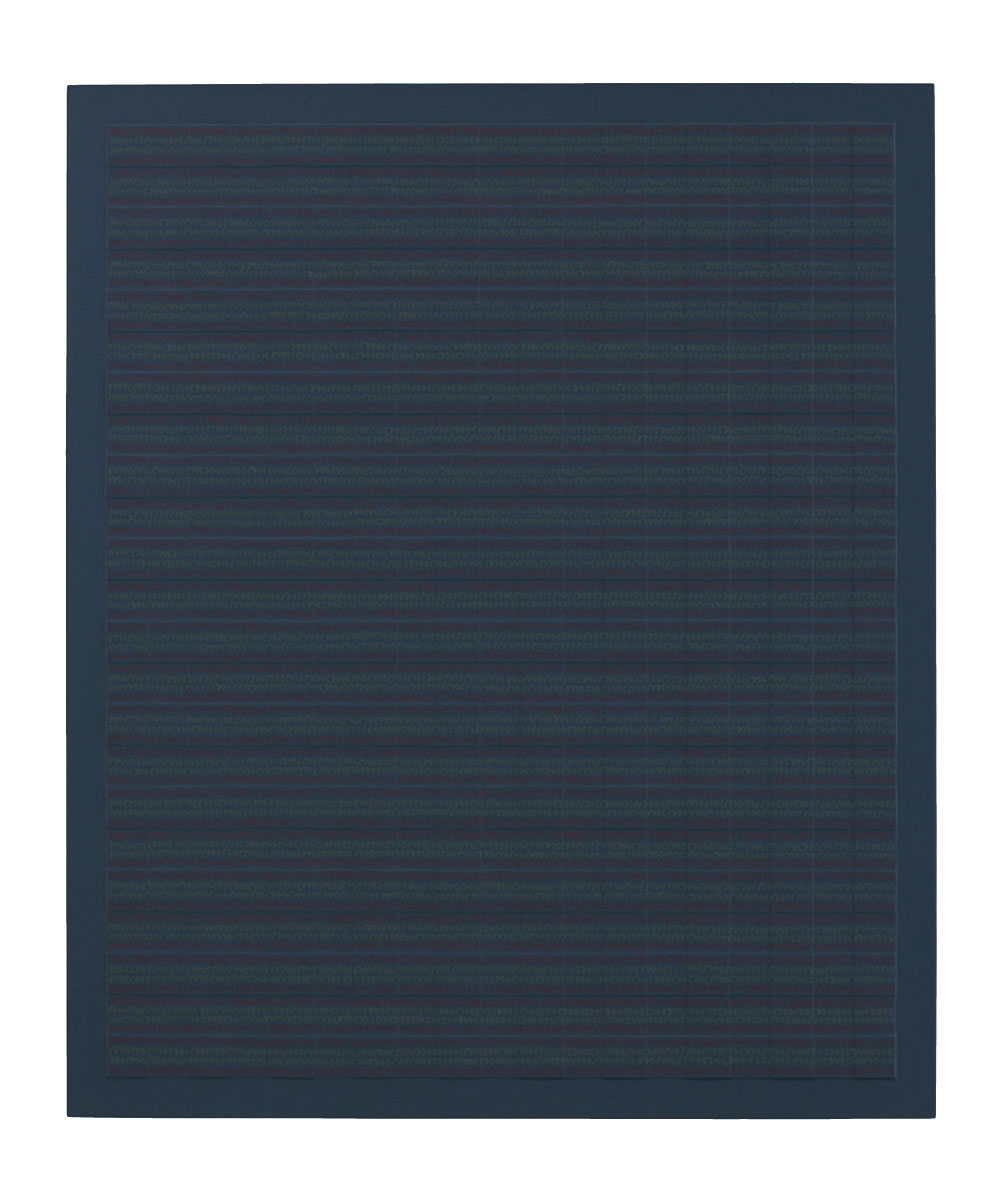

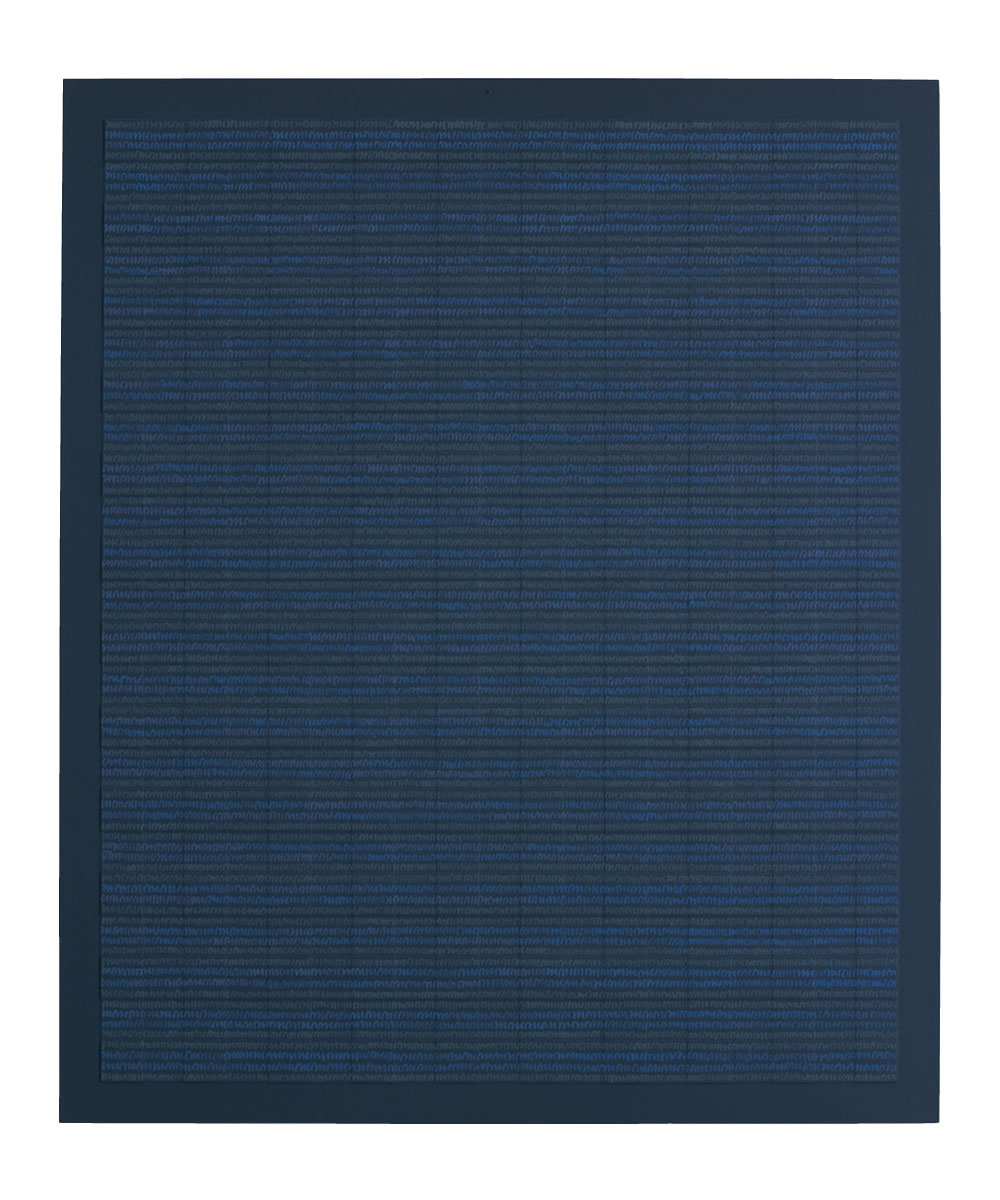

《Writing Over Squares on Canvas》では始めに、3種類の高さの違う正方形で画面全体を覆います。

これは描くことによって生じるイリュージョンの空間ではなく、非常に浅いレリーフ状による物理的な空間にするためです。

そしてこの上をデュクトゥス(Duktus筆跡)によって書き満たすことにより再び空間的なイリュージョンを発生させます。

このようにして生まれた絵画的空間は物理的な支持体の表面よりもわずかに奥にあり、同時にわずかに手前にあり、両者を行き来してビブラートしているような絵画空間です。

これが絵画空間の変遷の歴史における私の新しい提示なのです。

武蔵野美術大学美術館図書館2015年発行の図録 「KOICHI ONO A RETROSPECTIVE」から抜粋転載。

Why have human beings continued to paint a fictional space called painting on a physically flat plane?

I have been contemplating the answer to this through the two factors of "the plane as a material and the pictorial space as an illusion."

If you look at a picture with one eye closed, the perspective of whatever it is that is depicted appears more emphasized or stereoscopic than when you look at it with both eyes.

A human being judges the distance between himself and an object according to the angle of the lines connecting the object and each one of the two eyes.

If you look at it with one eye, this angle naturally is not formed.

Consequently, it is impossible to perceive the distance to the canvas and although the fact that the canvas is a plane can be understood from experience, it cannot be felt as a sensory perception.

Instead, the illusion depicted on the plane is perceived all the more frankly.

To put it the other way round, when looking at a picture, a human being perceives the physical plane and, at the same time, perceives the illusionary space depicted on it.

That is to say, he or she is having two contradictory perceptions at the same time.

However, it is indeed this contradiction that creates the pictorial space and the conflict caused by this contradiction is precisely what creates the complex, charming world of painting.

In my mind, the change in the situation of the conflict between the two factors of the plane as a material and the pictorial space as an illusion is actually the history of painting.

I feel that the basis of what Cézanne tried to do and what Mondrian tried to do lies here.

Once the camera was invented, the role of reproducing the actual space, which had been an important role assumed by painting until then, was no longer important.

Set free from the restraint of having to reproduce the depth in real space, modern painting began undergoing drastic changes in pursuit of a new appearance.

In the later examples of the Mont Sainte-Victoire series by Cézanne, the space between the foreground, the mid-distance, and the background shrinks rapidly.

At the same time, the figure-ground relationship created by the brushstrokes is not fixed so that it produces a shallow but opulent pictorial space.

In a picture of a pond in the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, the image becomes like an abstract painting in more or less green only.

There is even less depth in this painting, but the opulence of the pictorial space increases.

The figure and ground produced by the richly nuanced green color planes change places presenting an affluent pictorial space that you would never get tired of however many hours you kept looking at it.

The figure-ground relationship is an important element of the pictorial space in the famous series of works in which Mondrian abstracted apple trees, too.

In those works, which later reached geometric forms, the plane on the canvas as a material and the pictorial space painted on that canvas as an illusion reach more or less the same level.

Yet, the pictorial space is still slightly further behind the physical plane.

In Writing Over Squares on Canvas, I begin by covering the entire canvas with squares set at three different heights.

This is to produce a physical space in very mild relief that is not a painted illusionary space.

By covering these squares with ductus (handwriting), a spatial illusion reoccurs.

The pictorial space produced this way is slightly behind the physical surface of the canvas and, at the same time, slightly in front of it so that it appears to be imparting a vibrato by going to and fro.

This is my new presentation in the history of the changes of the pictorial space.

Passage extracted from the catalogue KOICHI ONO: A RETROSPECTIVE, published by Musashino Art University Museum & Library 2015